Lesson 32

9 years ago

Yeadon's Art Lessons

0

Titles

\

There is no such thing as the ‘purely visual’. All art comes with a text and a context. The viewer is more often than not told what to think, in all those books, magazines, reviews, labels and titles. All art is transformed by text and a change of context.

\

Most of this writing is by critics, journalists, reviewers, art historians, curators or gallery education departments and very little by the artists themselves.

\

In all this noise, titles are a way the artist has of giving the viewer a cue as to how they would like their work to be read or a clue as to their intentions.

\

Even ‘Untitled‘ used as a title is a cue. ‘Untitled‘ says that this is an autonomous, self referential work, to be viewed as a object in its own right. A genuinely untitled work would only be referred to as ‘untitled’ for archival needs. Of course titles are important for archival and cataloging purposes and here numbers are useful. Dating work is a good idea and would serve this cataloging need.

\

Even though the artist titles the work this does not prevent others changing the title, or the work being better known by another title. The painting colloquially known as ‘Whistler’s Mother‘ was in originally titled by Whistler as ‘Arrangement in Grey and Black No 1‘, which requests a very different reading from the conversational title commonly used of his pious Victorian mother.

\

For me titles have always been important; even the use of text in the image. Some students over the years have been reluctant to title their work, not wishing to pin the work down or be too specific as to what the work was about, which is understandable. But like images, language can be ambiguous and is often open to interpretation; if it wasn’t we would not have poetry or Shakespeare. Simply, these students needed to put more thought into their use of words.

\

There is the ‘non’ title, title, like a still life being titled ‘Still Life‘ or a landscape titled ‘Landscape‘ or, say, ‘Study‘. The viewer thinks that the title informs them of something but in reality this is an obsolete, redundant, anti-title that does not inform them of anything they don’t already know. This form of ‘innocent’ titling can be useful: for instance, imagine a painting of a murder scene titled ‘Interior‘, in which the understatement becomes poignant. Or the same scene contradictorily titled ‘Picnic‘, which would emphasise the macabre nature of such a painting. Titling work in a contradictory manner can be interesting.

\

Or take the honest descriptive and slightly shocking use of ‘street’ language in the titles of George Shaw’s work, such as the painting ‘Landscape with Dog Shit Bin‘, which refers to the intrusion of the urban and the managed into the rural. George Shaw’s titles are significant. Titling a banal fence of a feral scene ‘Ash Wednesday‘ not only gives the work a time of year but also a religious resonance, as does the series his ‘Scenes from The Passion‘. These melancholic paintings of unregarded, mundane, suburban hinterland are somehow contradicted and the viewer is challenged by these titles. The work should not fit the titles but they do. The viewer makes the fit.

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

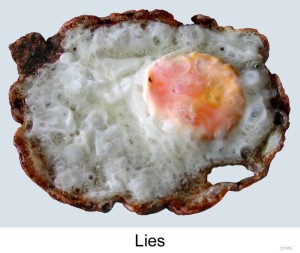

My series of digital prints Pabulum looked at random words juxtaposed with images of food. This was a collision of image and title. If the word initially made sense with the image it was rejected. So fish and chips with ‘Tradition‘ was rejected. Whilst a slice of corned beef titled ‘Threnody‘ and a fried egg with the word Lies underneath were fine. Words were only chosen if they did not make any sense. These irrational joinings and collisions were left for the audience to make sense of, for the viewer to make the connections. Again the viewer made them fit. (For Pabulum see here.)

\

Turning the sound off the television and turning the radio on always fits!

\

I remember a degree exhibition at Chelsea College of Art in the late 1970s. Chelsea was on the cusp between Modernism and Post Modernism, and there were minimal Modernist sculptures which should have been untitled or numbered but instead they had long poetic Post Modern titles. The titles were a desperate attempt to Post Modernise these late Modernist ideas. There were even works titled ‘Untitled‘ that also had a long obscure title in brackets; you cannot have it both ways.

\

Titling often comes when the work is finished, but can appear to the viewer as the initial idea for the work. I also recall being told about one year at Chelsea when students randomly chose books from the philosophical section of the college library, then randomly selecting a page and then a line which became the title of their work. This was very effective in upping the anti and the gravitas of the work. However, feigning intelligence or that you are well read is a dangerous game to play.

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

\

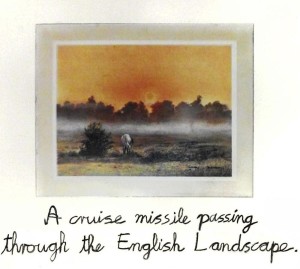

In a large drawing with a collaged reproduction of an idyllic painting of a horse grazing with the early morning mist rising behind, I inscribed underneath this reproduction ‘a cruise missile passing through the English landscape‘ which made the mist become the vapour trail of this weapon having zoomed passed. Nature serenely oblivious to the diabolical endeavours of man, akin to Peter Kennard’s juxtaposition of cruise missiles in Constable’s ‘Hay Wain‘.

\

A change of title can transform an image.

\

Imagine a George Shaw painting titled – ‘Arrangement in Grey and Black‘. Or the ‘Landscape Dog Shit Bin‘, alternatively titled – ‘Variations in Green with Red Spot‘. The paintings would be different. Not totally different, but different.

\

Lesson 32: Change the reading of a painting from art history by changing its title.

Change one of your own paintings with a new title.

\

\

\

\

\

\

This entry was posted on Friday, March 18th, 2016 at 3:03 pm

You can follow any responses to this entry through the RSS 2.0 feed.