Lesson 42

Dragged Up

The artist Liz/Stephen Rowe, a cross dresser, once explained to me the difference between ‘drag‘ and transvestism. Whilst many ‘straight’ men are cross-dressers, drag was “something homosexual men do for entertainment“.

Unfortunately, terms such as drag queen, female impersonator, cross-dresser, transvestite, even transsexual have become to some extent interchangeable today.

However, the drag artist exploits the false dichotomy between the sexes. The drag queen’s performance is a parody of fixed roles of gender and sexuality. Some feminists have criticised the drag artist for mocking women, but I think drag mocks men.

Cock in a Frock. Stephen Row. Self Portrait. 1987

The drag queen is fundamentally an ironic figure in his attempt to become the object of men’s desire and reveals the contradictions and difficulties being an effeminate man in a macho world. In the 1990s men were told to develop their feminine side. The media construct of the ‘New Man‘ was born, men used shower gels, gave women orgasms for the first time, and did the ironing. (well, in the TV ads. they did.) Yet, ‘effeminate‘ is still a misogynist insult, “the worst thing a man can be is to be like a woman“!

There is a sense that the only way this gay man on stage can be attractive or acceptable to men is to become a woman, which is further twisted as his audience would essentially be of gay men. The drag artist is an ambivalent character, like a holy fool, he has the authority to speak the truth, to speak out about what it is to be a ‘woman‘, to view the world in a different way to men, that is, the absurdities and contradictions of how gay men see the world.

Men have been performing on stage as women since Ancient Greek tragedies, in Shakespeare, to the comic Dame in today’s Pantomime or in Baroque Opera where we see early examples of what we understand as drag. Drag is in a long Carnivalesque tradition of the ‘world turned upside down‘. A man dressed as a woman is a provocative grotesque abomination, where insult becomes praise. In his book Rabelais and His World, Mikhail Bakhtin relates Goethe’s observations of a Roman Carnival of 1788.

‘Finally, the author (Goethe) presents an extremely characteristic scene which takes place in a side street. A group of masquerading men appears. Some of them are disguised as peasants, others as women; one of them displays the signs of pregnancy. A quarrel breaks out among the men, and daggers made of silver foil are drawn. The ‘women’ separate the fighters; the pregnant masker is terrified and her labor starts in the street. She moans and writhes while the other women surround her. She gives birth to a formless creature under the eyes of the spectators. Thus ends the performance.‘

Bakhtin sees this little scene played in a Roman side street as a miniature comedy of the body. The combination of killing and birth being characteristic of the grotesque concept of the body and bodily life. Birth and death in one.

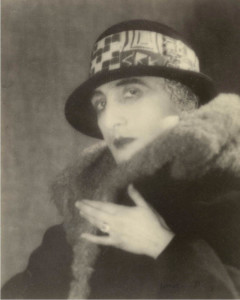

Whilst drag has a rich cultural history and has a strong position in popular culture, it has also developed a purchase within art. Androgyny and gender deception have a history in portraiture significantly with Leonardo as we see with the Mona Lisa or his St John the Baptist. We have Marcel Duchamp’s female alter ego Rrose Sélavy. Andy Warhol filmed drag queens and drag is one of the themes of Queer British Art at Tate Britain. There are of course cross dressing British artists Grayson Perry and Brian ‘Dawn’ Chalkley. Also artists such as Cindy Sherman’s fictional characters and Gillian Wearing’s masks enquire into identity, and more contemporary, in Victoria Sin there is a critique of the expectation of feminine Labour.

Marcel Duchamp as Rrose Sélavy by Man Ray. 1920.

Tony Threadgold* in his studio.

During a seminar on Art and Sexuality I suggested that the greatest distinction between men’s dress and women’s in Europe would be in the 19th century where the wealthy middle class Victorian male was not ostentatious but dressed modestly all in black like a 17th century puritan (the working class male was much more colourful and frivolity and flamboyancy was associated with the hated and lazy aristocracy). Though soberly dress this middle class man’s wife would exhibit his wealth, in a large dress and decorated with jewellery. Corsets, bustles and wire cages provided the substructure to this bondage of ownership.

However looking around the seminar group there seemed little difference in male or female attire amongst these young people, all wore jeans with a top, though no doubt the jeans were bought from gender-specific shops. Male and female jeans and t-shirts seems something of a paradox or unnecessary.

Until the Renaissance, European men often wore a type of skirt and today men also wear ‘skirts‘, not just Gaelic kilts or the Polynesian sarongs that have become fashionable in Europe but the clothing of Arabic North Africa, Africa, India and Asia. Trousers are less common in history and across cultures and are a recent more development in Europe, as is underwear.

Roman and Ancient Greek men and women wore underwear, loincloths or shorts called subligaculum were worn under a toga or tunic, but after the fall of Rome underwear (as in knickers or pants) were not worn until the late 18th century. There were Medieval ‘foundation garments‘ and evidence of bras were worn and from the 16th century women wore shifts or a chemise, corsets with whalebone and frames of wire and whalebone called a farthingale, where all these types of underwear were about creating the ‘feminine’ form.

Trousers and underpants were regarded as a symbol of male power and women wearing them were considered by the Medieval male as pugnacious wives trying to usurp the authority of their husbands, or were women of low morality. However the idea that women should not wear pants or draws does not mean that all women did not.

In the 18th and 19th centuries women had layers and layers of petticoats, underskirts and slips and generally nothing directly covering the genitals or anus. Even draws had a split crotch with little cover when legs were splayed. The probable absence of underwear makes it clear how vulgar and sensational the Can-Can originally could have been. Or, for instance Jean-Honoré Fragonard’s frivolous painting The Swing, also known as The Happy Accidents of the Swing, in which, the implication is much more obscene than cheeky or titivating once weunderstand that the woman on the swing would have been knicker-less.

The Swing. Jean-Honoré Fragonard.

The American women’s rights and temperance advocate Amelia Bloomer (though not inventing them) introduced and championed a type of underwear. The ‘Bloomers‘ named after her were a form of ‘dress reform‘ for women that was seen as healthy, sensible, comfortable and useful. Bloomers gave women greater freedom, metaphorically and physically. Bloomers became a symbol of reform and in the 1850s they became to signify women’s rights and the suffragette movement, offering a new level of independence and freedom, significantly the riding of bicycles. These dress reforms were also about improving women’s health through physical exercise and bloomers became standard ‘bicycle dress’ in the 1890s.

Aristocratic women resisted wearing bloomers stigmatising women who wore them as prostitutes or of low moral standing. We should not disregard myths around menstruation with the hostility shown to women wearing underwear. There was great opposition to bloomers, mocked in the press, with clergy and critics of women’s rights denouncing the wearing of pants by women as a usurpation of male authority, echoing the Medieval attitude.

Women in men’s clothing is very different proposal to men in women’s clothes. Women in men’s clothes can be much more controversial, they can also be invisible, and the drag king has a different comedy status than the drag queen. I am reminded of Kathy Burke as Perry in Harry Enfield’s TV series and recently Melissa McCarthy’s impressions of the US Press Secretary Sean Spicer on America’s Saturday Night Live.. But of course, these are character actors and not drag kings or cross-dressers.

Women dressed as men in the Middle Ages so as to get jobs and travel, they cut their hair and appropriated a man’s hat, before the 14th century women were primary distinguished by their headgear, later, styles between the sexes became more various. The swashbuckling Maid Marions as heroines in men’s clothing of Robin Hood films and the like, is a fiction, the wearing of men’s clothing would be perceived by the judicial system as a vice. The authorities wished to distance themselves from this practice regarding it as “erotic and alien”. Joan of Arc was accused of heresy, witchcraft and dressing like a man. Joan relented and signed a confession denying that she ever received divine guidance. A few days later, however, she defied orders by again donning men’s clothes and the authorities pronounced the death sentence. Dressing as a man was not a capital crime but for Joan it was a symbol of her calling. The 19 years-old Joan was burnt at the stake in Rouen on the 30th of May 1431.

Competing as a female artist in a man’s world, Rosa Bonheur the French 19th century animal painter, wore men’s clothes. The Empress Eugénie presented her with the Legion d’Honneur in 1865 murmuring “genius has no sex“. Women who disavowed traditional notions of femininity have been seen as being like a man, too strong, aggressive.

With men in skirts (whether this be kilts, sarong, the Arab thobe or other types of robes) women in trousers (pantaloons, knickerbockers or draws) we might wonder what distinguishes traditional male or female clothing?

It is within recent times that boys wore pink and girls blue and both wore dresses. This gender colour identification began in the early 20th century. Pink was deemed appropriate for boys and blue for girls, which was essentially a retail idea. This started to be reversed in the 1940s.

“The generally accepted rule is pink for boys, and blue for girls. The reason is that pink, being a more decided and stronger colour, is more suitable for the boy, while blue, which is more delicate and dainty, is prettier for the girl.” Earnshaw’s Infants Department. Trade Publication June 1918.

Given that pink was seen as a ‘stronger‘ colour than blue one might surmise that the pink being referred to was not the pale tint of red that we associate with ‘pink‘ today, but a bright red as in the scarlet of ‘hunting pink‘.

Since the 1990s and probably long before, masculinity has been in crisis, traditional male identity has taken several blows with the emasculating character of feminism. Not having a job, no longer the bread winner or ‘the man of the house‘. What is it to be a father? Even sexual desire towards women is somehow politically incorrect. The male is no longer the balcony from which everything is viewed. Our sense of what it means to be masculine is shifting, the new male position is tangible but still an incomplete metamorphosis.

Conchite Wurst is not a drag artist; however by winning the European Song Contest, cross-dressing seems to have begun to touch mainstream. Mick Jagger who in his androgynous performances challenged male stereotypes of masculinity noted that the British male has a predilection to drag up. Without little prompting the British male, on a charity fun run or a University rag week, would put on a dress as a grotesque parody of femininity. Jagger said that Americas do not understand this behaviour, presumably because they see any form of cross-dressing as sexual. The Queen video, ‘I Want to Break Free‘ (a parody on the soap opera Coronation Street) was controversial in the United States and banned on MTV and other stations.

Today the Drag Queen mocks the male sexual appetite. The drag performer is over the top, everything is exaggerated, his make up, his hair and his seven inch heels. He mocks the absurd lengths some women feel they have to or forced go to be attractive to men and the grotesque demands men make on women to be desirable. The drag artist will stumble in his high heels, he will pull on his bra strap and complain how uncomfortable it is or how long his makeup and hair took. He will wonder why women put up with these constraints. It is very important to see that there is a man behind this female facade, to reveal the male dragged up as a woman and not a man wishing to be female. The Drag Queen does not wish to pass as a woman, he is not impersonating a woman, nor is he expressing his ‘female side‘ nor that of a man more comfortable in female clothes or any fetishisation associated with female clothing. He is an entertainer who simply parodies male sexuality and desire.

*Tony Threadgold was a student at Coventry University and the Royal Academy in

the 1990s. He committed suicide in 2012. All these later works that explore

identity and his transvestism have been destroyed.

This entry was posted on Tuesday, May 9th, 2017 at 10:13 am

You can follow any responses to this entry through the RSS 2.0 feed.

Interesting article but devastated to read about Tony Threadgold.

I was at Coventry the same time as him .

I also remember a very drunken session with hom and John in London.

I went to primary school with Anthony back in the 1970s and early 80s. I used to go to his little stone cottage house for my tea after school and her come to mine. Hoppy days. Very saddened to read about what happened to him. I never knew he’d also become an artist. I’d have loved to have collaborated with him in one of my drag works- especially ‘Council House Movie Star’. Pity we never kept in touch. Rest in Power- Anthony.

Mark