I Can See His Lips Moving…

I Can See His Lips Moving, the Voices of John Yeadon

Introduction by George Shaw to the catalogue of the Fearful Symmetry exhibition, Lanchester Research Gallery, Coventry University Jan/Feb 2019

At some point in 1984, at the age of 17, I found myself in Coventry’s Herbert Art Gallery. There was nothing unusual about that as I often drifted in there half bored to death after not affording anything in Hits and Misses record shop, loitering in Gosford Books and studying art students coming and going from The Poly or The Oak. But on this day there was something different to be had lurking amongst the stuffed animals, dusty Godivas and Graham Sutherland’s leftovers. And that was John Yeadon’s Dirty Tricks. I don’t think I’d ever seen contemporary painting in the flesh before that day. I didn’t think it existed to be honest. The patches of art history, which I discovered in the library or through TV documentaries was as remote as all history is to a teenager. I was aware of Francis Bacon hanging around in the shadows of London and I’d read Hockney by Hockney (a kind of Billy Elliott scripted by Alan Bennett) but they could have both been long dead for all I knew. So what on earth was going on here at the Herbert Art Gallery? And who the fuck was this John Yeadon?

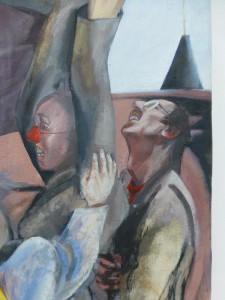

For a start off the paintings were huge. I could see what was going on in them from the other side of the room, bright and clear, as though they were advertisements. Some had writing on them that looked more like the graffiti on the garages. Some had stuff stuck on them like a dead squirrel or a mattress and even a bit of neon. Some of the figures were well drawn like life-drawing and others looked like the kind of scribbles you would find on the back of a toilet door. Some parts of the paintings looked unfinished like someone didn’t give a shit. I found myself laughing and wondering if you were allowed to laugh in art galleries. Bits of it was like a Bacon but if he’d got out more and other bits were like a Hockney but with balls and that’s saying something, I think. I remembered thinking what would it be like if I made paintings that looked like this? What would the teachers think? What would my mum and dad think? What would I think?

After a while (perhaps I went back on another day) I discovered that these paintings had a subject matter and what most impressed me was that subject matter seemed to be the world I lived in. Curiously the way in which the paintings were made spoke to me about a real life too. Half history painting with dashes of advertising and graffiti, dollops of porn and scatological gestures. There were references to the Falklands conflict and the common anxiety about nuclear warfare. There were interiors that looked like the kind of rooms people lived in with unmade beds, TVs and Christmas decorations. There was even a painting of a computer. There was nudity, lots of it, and an uncensored eroticism. All in all there was a sense of chaos. Strangely, there was a feeling of the British landscape with its buses and pubs and pokey houses but it was a landscape of aftermath; which if you had any wits about you was exactly the Britain of the early eighties. And amongst it I could see individuals sticking their two fingers up to established order and their arses up to the world.

This isn’t what I was used to art doing or being used for. Or perhaps, more precisely, what art actually is. When I read the catalogue essays it confirmed that the intention of the painter was disruptive. They emerged from a background of social and political injustice giving voice to the lives of the silent. In his writing Yeadon says ‘for me the problem is a straightforward class issue: to challenge high art traditions and formulations, to make an intervention into the fortress of bourgeois ideology and to violate taboos’. And with that all sorts of reference points are dragged up from Lenin to witchcraft and nuclear threat, from Bosch to Goya, Rabelais and Burroughs, there’s paganism vs Christianity, high brow vs low brow (whatever they are) and the taboos associated with sexuality and bodily functions.

I’d heard similar voices in pop and seen it on TV. These were the voices and the visions I recognised. Coventry’s own The Specials had hit the charts with an anti-racist stance and kitchen sink lyrics you could dance to. Post punks and the rising independent music scene of the early eighties had given a generation of teenagers an education in left wing politics and articulated a subcultural disaffection. In 1981 the band the Gang of Four sang ‘to hell with poverty lets get drunk on cheap wine’ prompting me to ask my dad what a communist was. TV series like Alan Bleasdale’s Boys from the Black Stuff or Alan Clarke’s play Made in Britain showed a country far removed from the promised lands of Thatcherism. And there was a humour in John’s paintings that made me think of The Goodies or The Young Ones even: all farts and funny faces.

All of that could not have been further from the world of art I saw at school or in the library and yet here it was on the walls of the local gallery. And yet it turned out that one of my teachers, Miss Kenny, knew John Yeadon. I don’t know when or where it was but it wasn’t long after I saw Dirty Tricks that I met John. I remember thinking that this was the first real artist I’d ever met. He was talking constantly and smoking and drinking so maybe it was in The Oak and I was very impressed.

John certainly looked like the author of the paintings I saw. He looked like them and sounded like them. It was and remains convincing. There was always something self consciously theatrical about the paintings in Dirty Tricks. Indeed one painting did show a stage curtain either opening or closing (you decide) with the title Political Painting (The National Debt as seen as a Political Drama). The characters perform on a series of stages and the titles are like prompts. John acknowledges himself as a director of a drama of sorts. The music hall is never far away in his use of jokes, of nudge nudging and acknowledgement of the viewer or audience. It is not surprising then to find out that he comes from a theatrical family. His mother and grandmother were ventriloquists as was his great uncle. Artists themselves make inanimate materials speak or, at least, try to. Valentine Vox writes in the preface to his History and Art of Ventriloquism, called after the familiar criticism, I Can See His Lips Moving, that ‘during the so-called Dark Ages, exponents were regarded as demonic conjurors possessed by unclean spirits that lurked in their entrails, whence they gave their utterances. The practice of ventriloquism often resulted in imprisonment or death.’ Ventriloquism means belly speaker and that implies the speaker of truth and such speakers are often a threat to a ruling order. The ventriloquist act I was most familiar with was Ray Allen and Lord Charles on 1970s and 80s TV. The dummy was often seen as an innocent in the world of people. Oddly enough Lord Charles is an upper class toff in contrast to most of his audience (there is a whiff of the Jacob Rees-Mogg about him). Consequently he could be insulting and rude and just about get away with it. There was always something uncanny about the act too; an ever-present psychological fuck-up that artists can be heir to. John’s paintings of ventriloquist dolls that have passed through his family are some of the creepiest paintings I’ve ever seen. It’s as if he wants to bring them to life, at least to make them speak. What makes them uncanny is their realism. The painting warms the dummy up to flesh and blood. Such acts are not uncommon in studios. Birmingham City Gallery has a series of paintings by Rossetti that show Pygmalion sculpting and coaxing his marble sculpture of Galetia from cold white marble to a rosy eroticism (she seems to acquire clothing too). Didn’t Kokoschka commission a realistic doll with hair in all the right places to replace his lover? Wasn’t it Poussin, not a stranger to the pagan myths of Pan and Bacchus, who said of himself: ‘I who make a profession of mute things’. At times I’m reminded of the wonderful and disturbing drawings Nilsen did of his victims entitled Monochrome Men, Sad Sketches reproduced in Brian Masters’ Killing For Company. They are all attempts at animation or reanimation as a way of dealing with loss. The ventriloquist finds the dummy’s voice.

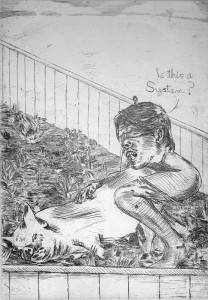

It was only a matter of time before John had his own dummy. And in comes Blind Biff. He is as alive as anyone can be. He has a thoroughly convincing genealogy dragged from the myths of old maps and travellers tales. Looking like he was shoved off the stage of one of the Dirty Tricks paintings Biff is seen wandering through a timeless Britain sticking his naïve nose into folklore, customs, landmarks and taboos. John comes across as Biff’s straight man documenting his travels like a curious uncensoring Boswell. But like most straightmen he leads his partner into situations he can play to. We see him in Blackpool, at parliament, celebrating Christmas, at Marx’s grave in Highgate, masturbating and even fucking a pig (in an unauthorised biography of David Cameron it was revealed that he put a ‘private part of his anatomy’ into a dead pigs mouth during an initiation ceremony to some Oxford society so yes, Biff, it is a system).

John has written eloquently on the role of the fool and the clown within cultural traditions and the importance of carnival and a world turned upside down. As he says again and again laughter is a symptom of revolution as are some forms of dance and ritual. Elements of Biff’s adventures remind me of Homer Sykes photographs of folk customs acted out in a landscape of 1970s Britain. Such images reveal and revel in a defiance of an inevitable modernity and show a humanity quietly and heartily being itself. Photographers like Sykes documented a Britain they saw being ignored, unheard and unrepresented. It was world that didn’t fit the capitalist narrative of relentless growth and greed. Biff’s wandering gives life to this world in all its richness and vulgarity and he does it with a grace and a curious respect. The term humour, of course, derives from Greek humeral medicine and refers to the balance of bodily fluids. It implies life and humanity.

I was so impressed with John’s Biff series that I did what any young art student would do and ripped it off. In 1989 I may have called it homage but my own figure of Jack Bastard was Biff’s illegitimate offspring. Perhaps it was myself finding a voice.

But we know it’s a trick, a dirty trick maybe, an old trick definitely. The dummy is not alive and its voice is the voice of the ventriloquist himself. A life’s work of any artist can be seen as self-portraiture. It all comes down to that in the end because what else can we do? John does appear in a few of his painting over the years but it is in the figure of Biff that he most evident. Speaking with him recently he talked about the contemporary craving for a back-story and he wondered if he should offer one. But that’s a literary device or another trick used to sell a book or promote a wannabe. What John has given us is a voice, a voice that speaks a truth. It shows the artist as any self-portrait does but it also reveals a truth about ourselves and the world in which we live.

George Shaw, October 2018

.