The Nineteen Eighties

The Nineteen Eighties

[Text written in association with Fun Factory, Lanchester Polytechnic Faculty of Art and Design 1980-1983. An exhibition of photography by Alan Van Wijgerden.]

The 1980s was a significant decade for me. And the Art Faculty at the then Lanchester Polytechnic in Coventry.

Though teaching full-time in Fine Art at the ‘Lanch’, in 1982 I had a residency in Prague as a guest of the Czech Artists Fund on the 40th anniversary of the destruction of Lidice; in 1984 My Dirty Tricks exhibitions were held at the Herbert Art Gallery and Museum in Coventry and the Pentonville Gallery in London, and Happy Families at the Lanchester Gallery, Faculty of Art and Design at Coventry Polytechnic; 1986 saw my one person exhibition at the Transmission Gallery in Glasgow.

I began work on my Blind Bifford Jelly series during the 80s with the first exhibition at the Lanchester Gallery in 1988. This series was later to be exhibited at the Ikon in Birmingham, Centre for Contemporary Art in Glasgow, the Royal Festival Hall and Vilma Gold in London.

I was a contributor to a number of group shows during this period, including 21 for 21 and the British Art Show at the Ikon Birmingham (and touring), the State of the Nation at the Herbert in Coventry, Critical Realism at Nottingham Castle and Invisible Man, Representations of Male Sexuality, at Goldsmiths Gallery in London.

At this time I was also a visiting lecturer at Goldsmiths, the Slade, Duncan of Jordonston College of Art, Dundee, Middlesex, Oxford, Sheffield and Trent Polytechnics and Hull College. I taught Mark Wallinger at Goldsmiths and George Shaw, Jonathan Waller, Paul M Smith, James Lloyd, James Jessop, Sid Norris, Peter Lelliot, John Riddy, Russell Haswell, Keith Piper and Eddie Chambers among many other now successful artists who were students at Coventry during this time.

The 1980s began with an explosion of riots in Brixton, Handsworth, Chapeltown and Toxteth. In 1981, Britain was in the middle of a deep recession, unemployment rose to 2.5 million. The TUC’s People’s March for Jobs from Liverpool to London was an attempt to put pressure on the government to redress the problem. Also in 1981 were the Irish hunger strikes and the contrast of the Royal wedding of Prince Charles and Princess Diana.

There then came the 1982 ten-week-long Falklands Conflict, the Greenham Common Women’s Peace Camp, the 1984-85 miners’ strike with the Battle of Orgreave and a re-escalation of the troubles in Northern Ireland which peaked with the attempted assassination of the entire Tory Cabinet in the Brighton bombing. The Broadwater Farm Riots were in 1985. There was the economic Big Bang of 1986. The King’s Cross underground station fire in 1987. In 1988 we saw the Section 28 ruling, which banned the ‘promotion’ of homosexuality as a ‘normal family relationship’. It was a time of AIDS paranoia and imminent nuclear threat, which breathed new life into CND. The decade ended with protests at the introduction of the Community Charge – the Poll Tax – and by British Muslims against the publication of Salman Rushdie’s Satanic Verses, with the Hillsborough disaster and the massacre in Tiananmen Square also in 1989. In the final weeks of the 1980s, the Berlin Wall came down.

Some things were uniquely of that decade, but the 1980s also introduced and sowed the seeds of many things which are familiar to us today.

As today, during the 1980s Britain was a polarised nation. Some Britons rioted and went on protest marches whilst others bought shares in the newly privatised ‘Tell Sid’ gas industry and bought their Council Houses. Some women displayed their naked patriotic breasts in welcoming soldiers back from the Falklands.

Britain was no longer the workshop of the world: there was mass privatisation, the beginning of the loss of the British manufacturing industry and deregulation of the financial markets and the City. Where Rationalisation meant asset stripping, creating industrial wastelands. It saw the decline of the Trade Unions and of greater inequality. Of trickle-down economics and Monetarism where governments control the amount of money in circulation. A time of high interest rates and soaring sterling exchange rates. In 1983 for the first time manufactured imports exceeded those exported. Upward mobility also began to cease.

There was no Internet. No smart phones – though 1983 saw the first commercially available portable cell phone. However there was the Filofax, Walkmans, shoulder pads, big hair. Yuppies. Lager Louts. Alternative comedy. MTV, House Music, Live Aid. Princess Diana. Dynasty, Dallas, Saturday Night Live, The Young Ones, Red Dwarf, Only Fools and Horses, the Kenny Everett TV Show and Hi-Di-Hi. With the Rubix Cube, DNA fingerprinting, Breakfast TV, VCR, IBM and Macintosh personal computers, disposable cameras, the space shuttle, Prozac, the F-plan diet, Nouvelle Cuisine, bottled water, New Romantics and New Expressionism.

It was Margaret Thatcher’s decade. Her tenure lasted from 1979 to 1990, and the ‘Iron Lady’ was the bridge between her American ‘partner’ Ronald Reagan and the man ‘she could do business with’, Mikhail Gorbachev. The Soviet-Afghan War lasted 9 years from 1979 to 1989. America and Pakistan backed the insurgent Mujahedeen with Saudi Arabia offering financial support. Osama bin Laden joined the Mujahedeen in 1979 and founded al-Qaeda in 1988. Soviet forces withdrew under Gorbachev, leaving Afghan government forces to battle insurgents until 1992. We had Glasnost (openness) and Perestroika (restructuring) and towards the end of the decade we saw détente and nuclear disarmament deals and the beginning of the ‘Cold Thaw’. With the Berlin Wall coming down the GDR became part of the Federal Republic in 1990.

It Took a War

At the beginning of her time in office, Margaret Thatcher was extremely unpopular amid recession and increasing unemployment. That is, until the Falklands Conflict, after which she became one of the most popular Prime Ministers. Though the first woman PM in Britain, her leadership style was dictatorial and authoritarian. Thatcher did not believe in ‘society’: that is, that there was such a thing as society. She openly stated that people should also have the right to be unequal and that you were a failure if you were over 30 and still travelled on a bus. She cut social welfare programmes, reduced Trades Union power and influence, privatised state owned industries, deregulated the financial industries and allowed the purchase of Council houses.

Greed is Good

Known as the Decade of Greed, the 1980s slogan was for many “Get rich, borrow, spend, enjoy”. There was conspicuous consumption and yuppies flaunted dosh unashamedly.

Ghost Town

By the 1980s Coventry had one of the highest unemployment rates in the country. There was a major rally in Coventry to welcome the marchers on the People’s March for Jobs from Liverpool on their way to London. The 15 top employers in Coventry cut their workforce by a half. The manufacturing of cars was in terminal decline along with the collapse of Alfred Herbert, once the world’s biggest machine tool firm. In spite of a high level of unemployment – or because of it – pubs, clubs and nightlife flourished. The city had a high crime rate and acquired a reputation forviolence. The Oak was the art school pub, packed at lunchtime and in the evening. Run by an Irish couple Jim and Babs from Longford, their Irish tricolour had been taken down after the IRA bombing in Coventry in 1978.

The era-defining song ‘Ghost Town’ was released by The Specials’ in 1981. Written by Jerry Dammers after driving through Glasgow, ‘Ghost Town’ was regarded as a ‘prophecy of doom’. In 1981 the Rock Against Racism concert was held at the Butts Stadium, organised and headlined by The Specials.

It Took a Riot

The report ‘It Took a Riot’ by Michael Heseltine when Environment Secretary is the Daddy of urban renewal. Contrary to Thatcher’s free market ethos, Heseltine made £270 million available for urban development in 1981-2 as a response to the Toxteth riots. The restoration of the Canal Basin Warehouse in Coventry benefitted from this policy and was therefore indebted to the Liverpool riots. At Heseltine’s suggestion a Garden Festival took place in Liverpool, which bizarrely was supposed to help to revitalise Liverpool. This misguided festival was directed at the problems and issues that Toxteth faced and despite being named European City of Culture in 2008, Liverpool still has severe problems.

Coventry, a City of Culture

The Herbert Art Gallery had significant exhibitions, many curated by Patrick Day. There was the International Festival of Video Art 1978, the Pan-Afrikan Connection in 1983 by the BLK Art Group who were later to have international recognition. (Eddie Chambers and Keith Piper studied on the Foundation Course at Coventry Polytechnic in 1979). There was Tradition and Renewal, Contemporary Art in the GDR exhibition in 1984 at the Herbert curated by Oxford Museum of Modern Art.

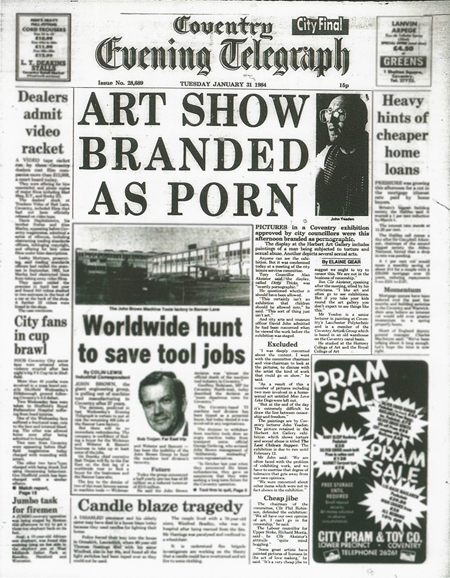

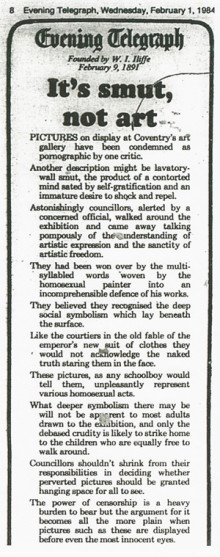

Also, in 1984, my exhibition Dirty Tricks, which was condemned on the front page of the Coventry Evening Telegraph as pornographic and accompanied by homophobic editorial rant. (Though the exhibition increased the attendance at the Herbert by 40%). Works from this exhibition were later exhibited at the Pentonville Gallery in London and the British Art Show of 1985. An exhibition of Peace Banners at the Herbert also came under fire in the Coventry Evening Telegraph by a leading Tory Councilor. Cllr. Helen Cooper was dismayed by the thought of the display of peace banners that would coincide with the city’s peace week in November. She told the city’s leisure services committee “A lot of banners are a symbol of incitement”. A local example of right-wing paranoia, which regarded the peace movement as a communist conspiracy and the leaders of CND as Soviet agents.

The State of the Nation was an exhibition in 1987 organised by Sara Selwood when all the walls of the Herbert were painted black. This politics and art exhibition featured Stuart Brisley, Rasheed Araeen and myself amongst others. It demonstrated that the art of the 1980s was born out of the society in which we live, an art capable of representing the ideas of the time. There were also many important individuals exhibiting at the Herbert such as Paul Butler, Gary Wragg, Anthony Green, Pete McCarthy and Lowry.

Dick Whall (who was Head of Media on the Fine Art Course and became the Head of Art at Coventry Polytechnic) had a solo exhibition at the Mead, Warwick Arts Centre and both Dick and myself had solo shows at the Ikon Gallery in Birmingham. The 21 for 21 exhibition in 1984 at the Ikon celebrated the Ikon’s 21st birthday with 21 Midland artists that included a number of Coventry artists. This would be unlikely or impossible today for Midland-based artists to show at these galleries. Also today, the Herbert Art Gallery rarely curates its own exhibitions but like the Meade ‘buys in’ already touring exhibitions and it is worth noting that £20 million was spent on redeveloping the Herbert, resulting in less space for painting than they started out with, and one Gallery even lost to storage. This is not just incompetence, but represents a victory of Social History over Art at the Herbert. However, it is with a radical curatorial policy of contemporary art that will bring in the visitors, as the 1980s experience demonstrates.

History is continually being revised to fit the needs of the time and to suit the fashions of the day. The Ikon Gallery’s exhibition in 2014 for the gallery’s 50th anniversary, reviewed the exhibitions the Ikon had in the 1980s. As Exciting As We Can Make It did not include any of the New Painting, the return to figurative painting that for many characterised this period. Even the 21 for 21 exhibition was missing from the list of 80s exhibitions in the Ikon’s catalogue. In response, after viewing the exhibition, I told Jonathan Watkins the Director of the Ikon that the exhibition did not adequately represent the 1980s, the 80s being, for me, more “miners strike and AIDS”!

History is continually being revised to fit the needs of the time and to suit the fashions of the day. The Ikon Gallery’s exhibition in 2014 for the gallery’s 50th anniversary, reviewed the exhibitions the Ikon had in the 1980s. As Exciting As We Can Make It did not include any of the New Painting, the return to figurative painting that for many characterised this period. Even the 21 for 21 exhibition was missing from the list of 80s exhibitions in the Ikon’s catalogue. In response, after viewing the exhibition, I told Jonathan Watkins the Director of the Ikon that the exhibition did not adequately represent the 1980s, the 80s being, for me, more “miners strike and AIDS”!

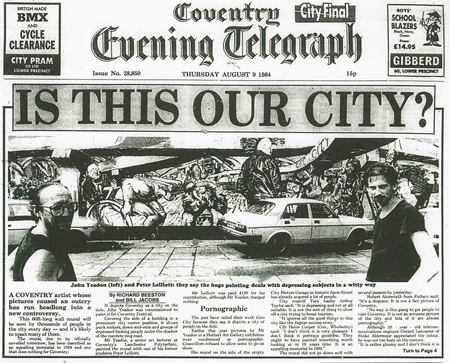

Jeremy Vine first worked as a journalist at the Coventry Evening Telegraph in 1986. Vine, in a recent video in support of the City of Culture bid, talked about “the underside and the downside” that “art is created in places where it is difficult, a city where people struggle“. His example of this hard living was The Specials’ Ghost Town. Undoubtedly a romantic view of the artist, but I don’t think the Coventry Evening Telegraph or Coventry councilors have ever appreciated this analysis, if you take their response to Peter Lelliot’s and my mural ‘Giro City’ for the Coventry Arts Festival of 1984 as any kind of measure. I pointed out to the Labour councilors, who thought that the mural was drab and negative and did not tell the whole story of Coventry, that the title ‘Giro City’ was a quote from their leader, Neil Kinnock, who said that ‘Margaret Thatcher was turning this country into the Girolands‘. The mural was not negative, but showed multi-cultural, working people [including a miner] – people in struggle and people who are not usually celebrated in paintings. What could be more positive than a disabled athlete speeding in a wheelchair? All ignored by the Coventry Evening Telegraph who even managed to get the word ‘pornography‘ into their article.

The mural was criticised for depicting so called ‘down and outs’. Later in 1988, characterised as a pioneering crackdown, a by-law was passed to prohibit the consumption of alcohol anywhere in public within the city centre. The excuse cited was problems with ‘lager louts’, its effect was in fact aesthetic and cleared the derelict and dispossessed from the city centre to beyond the ring road. Out of sight out of mind, criticised by many as sweeping social problems under the carpet and not addressing the needs of the homeless and alcoholism in any fundamental way.

Students

Students sometimes came with a van to their interviews, that is, a van full of work, of large paintings, the interview having to then take place in the Lower Ground Floor corridor, not being able to transport the work in the lift. It has been said that, these days, rather than vans, students bring their parents to interviews. In the 80s going to an art school far away from home was an ‘official’ way of running away from home. Now, because of finance issues, many students have to apply to their local University. At this time, students received maintenance grants and their fees were paid by their local authorities, but by the end of the decade we saw diminishing student grants and the introduction instead of student loans. Many students lived in what would be regarded today as squalor, in Stoke and the Foleshill Road. This was in private landlorded accommodation in houses of multiple occupancy; the image of student living as portrayed in the Young Ones was not far from the truth. At the 3 Binley Road squat, there was a hole in kitchen ceiling from which you could see toilet above and it had leaking sewage in the garden. Some students lived in a ‘bender’ a DIY beehive dwelling and in a teepee in the garden. From 1987, 3 Binley Road was to become the popular Stoker music and arts venue, now demolished for the Sky Blue Way.

Books not Bombs

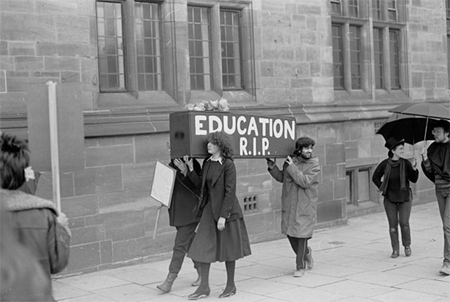

During the 1979 sit-in protest against cut-backs in arts education, a Foundation Arts student abseiled down the front of the Art Faculty and four others were arrested and fined for painting ‘political’ graffiti around the Polytechnic central quadrant, the latter incident making the front cover of the Coventry Evening Telegraph, of course. The Art Fac lost staff and resources, and courses were rewritten to accommodate these cuts, a process which carried on in the next decade more easily with the University’s self-validation of courses. Students organised a letter-writing campaign against the cuts which got into the national press, and there was a work-in in 1982. In the main, most staff supported their students during the work-in which placed them in a difficult position with the Poly authorities as some were blamed for instigating the occupation. The Polytechnic’s Critical Art Group’s exhibition was banned from the Glass Box Gallery (Architects Showroom, as was) – it might have been the drawing of the Queen sat on the loo reading the Sun newspaper that tipped the balance! Labour councilors defended the ‘artists right to be critical’ sighting Goya as a precedent. There was also the ‘Car Parts for Food’ performance by Fine Art students outside the Art Fac.

Death of a Thousand Cuts

However, despite the cuts, Fine Art maintained its broad, pluralist and interdisciplinary course for the most part in the 1980s that it had established in the 1970s. Offering painting, sculpture, printmaking, photography, video, film, animation, performance and art theory, not just as media resources but also as Degree options. Students had free materials, sculpture included many fabrication processes including hot-metal casting, fibreglass, plaster, stone and woodcarving, and there was even a tradition of using ceramics in Fine Art at Coventry. This was supported by full-time staff and technicians with additional expertise and experience provided by a host of part-time staff. There were also three full-time lecturers in Printmaking with two technicians. As academic staffing the Media Centre had full-time lecturers in photographers and film, and Steve Partridge (video) and Max Eastley (sound) as part-time lecturers. There was an Art History and Communications Dept., a library and a canteen on the 2nd floor. In 1987 the Digital Media course was the first electronic art and design postgraduate course in Europe. George Shaw was a student on the Foundation course in 1985 and Graham Crowley, Michael Porter, Teresa Oulton, Adrian Searle were amongst the visiting lecturers in Painting.

In the 1980’s Coventry had 6 Principle Lecturers in Fine Art, (Head of Fine Art, Course Tutor, Head of Painting, Head of Sculpture, Head of Printmaking, Head of Media). Today there is just one Principle Lecturer overseeing Fine Art, Foundation, Illustration, Graphic Design etc. This is a measure of the ‘efficiency’ changes that over a decade of cuts has delivered. For staff and students alike, there used to be a sense of ownership of the course. Later, students became clients and the academic staff were simply employees delivering a course in a University and no longer belonging to an art school.

We had the annual Cabarets, which became the Gong Shows raising money for the Degree Shows’ exhibition catalogues. Colin Saxton, the then Head of Art, and other staff enthusiastically took part in the Cabarets with their own acts. Events Week was an annual international performance and video festival organised by the students, which took place in the Media Centre. The students even employed members of the academic staff to work during Events Week. At one event there was a fashion show of second hand clothes and a hair cutting ‘salon’ in the Student Union Downstairs Bar, during the evening there was a performance that involved students smashing up a piano with an axe, then, getting a bit carried away, also smashed up the other piano which belonged to the Students’ Union. Steve Partridge and myself decided that we had not seen this.

Unbelievably, staff and students smoked in the studios, in lectures and seminars, in the offices and at formal academic meetings.

New Lamps for Old

‘History has stopped. Nothing exists except an endless present…‘ George Orwell 1984.

By the 1980s we were well into the Post-Modern era of irony, anti-intellectualism and anti-ideology, with a preoccupation with appropriation, re-contextualising, ‘retro’, nostalgia, parody, pastiche, cultural cannibalism, repackaging, rebranding, quotations and art historical and popular culture reference. The pluralistic, ‘pick’n’mix’, free-for-all attitude to art production. It was a fresh, exciting time of breaking with the formality and restrictions of Modernism. A liberating time when large figurative painting became dominant. By 1979 the whole of the degree show in painting was figurative at Coventry. This re-introduction of figurative imagery – a new discordant and overtly expressive imagery, embraced literature, history, and story telling and its subject matter concerned the realities of the modern world. Conceptual artists became figurative painters, as did video artists and performance artists, even most abstract painters eventually painted representationally. However as Sandy Moffat pointed out “the extravagant promotion and huge market success of New Painting turned it quickly into an international fashion and encouraged work which was little more than feeble pastiche”.

The Freeze exhibition in 1988, held in an empty London Port Authority building in London Docklands, gave birth to the Young British Artists (the YBA’s), who were, at the time, considered radicals. The exhibition organised by Damien Hirst consisted of, essentially, students from Goldsmiths’ College and was seen as an alternative to the art market. In the same year Coventry students had their degree show in an empty warehouse in the industrial estate that has now become Fargo. The YBA’s caught the attention of Norman Rosenthal, the Exhibitions Secretary at the RA, the academic ascetic Nicholas Serota and Charles Saatchi, the advertising mandarin who made his pile promoting Thatcherism. Yet again, as it is with most enfant terribles, the YBAs turned into the edifice of the Establishment and international art market. These artists were Thatcher’s children, and by the 1990’s they had embraced the art market; unlike previous generations, they were not sceptical about the capitalist nature of the art market, a market which had grown inextricably since the 1970’s.

Coventry Polytechnic became a University in 1992 taking it out of local authority control. Coventry School of Art was 150 years old in 1993 a celebration which was hijacked by the newly instated University claiming it as the University’s own anniversary. The School of Art was thus totally absorbed by the University. As Jon Thompson, Head of Goldsmiths department of Art, put it “art and design sold their inheritance for a mess of University potage“.

John Yeadon, November 2017

Acknowledgments, and thanks for jogging my memory go to Alan Dyer, Dick Whall, Jonathan Waller, John Harris, Ruth Longoni, Dave Cooper. Photographs by Alan Van Wijgerden.