Englandia: the paintings of John Yeadon by Nick Smale – 2015

[Published in ARTSPACE, the journal of Leamington Studio Artists, Issue 42.]

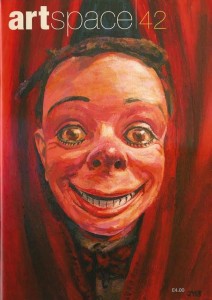

The way a past is brought back to life, so past and present may coexist, is vividly achieved in John Yeadon’s painting, Suitcase Act [1], one of many portraits and landscapes exhibited at the 150 Gallery in February this year. The painting is a portrait of ‘Tommy’ [2], a ventriloquist’s dummy, owned by the artist but originally the property of Helen Yeadon, an amateur ventriloquist and Yeadon’s mother. Yeadon’s uncle, Maurice Howarth, also a ventriloquist (and magician) is the last in the line of a family of ventriloquists, of which the most celebrated was ‘Madame Langley Lady Ventriloquist’ who toured the music halls for twenty-one years from 1911 and played, second on the bill, at the London Coliseum and Moss Empire theatres. Madame Langley had several dummies two of which, Johnny Green and Annie, are featured in the exhibition [3].

Yeadon writes that “Tommy’ is “…less malignant and tyrannical than Mr Punch or Ubu, more Puck like” and is related to that other world, which has been characterised by Bakhtin as a “second world….a second-life outside officialdom” [4] – the world of carnival, a world turned upside down – when for a few days each year lawlessness prevails, comedy is liberty; a non-official time of “anti-dogma, anti-protocol, anti-serious spectacle”. The ‘Drunken Jolly Jack’, the carnival’s ‘Lord of Misrule’ is represented in the exhibition by Yeadon’s painting entitled, Jolly Jack Tar. Yeadon writes that such fools “..are more than social critics, they are purveyors of free speech. The fool knows the truth as he is a social outcast”.

To focus solely on the conceptual aspects of Yeadon’s work would be to overlook the quality of his paintings as paintings: the skill, imaginative flair, verve, panache – éclat with which they are painted. There are some twenty-nine in all. Executed over a period of four to five years, these portraits, together with three larger paintings, Jolly Jack Tar, Laughing Sailor and Sydney Knows (front cover), stand as a testament to Yeadon’s devotion and affection for the characters he has brought to life. Part personal history, part conceptual, they may be seen as an exploration and recovery of an important aspect of his family history; the shoes that ‘Tommy’ wears are the shoes Yeadon wore as a boy. He has painted their scuffed soles, not scuffed by ‘Tommy’ but by Yeadon himself. However, the implication in the painting is, that ‘Tommy’ has been secretly going for walks! Conceptually the portraits represent an aspect of our culture, of Englandia, defined in the OED as “a humorous fictionalised, metaphorical concept of England and Englishness”.

This family of ventriloquist dummies is, Yeadon writes, “in between autobiography and fiction ….. The ventriloquist’s doll is a fake human being, it is a fraud, it is artifice, like a three dimensional caricature or cartoon that comes alive”. The life that they have as paintings, staring back at us from the walls, is achieved by Yeadon’s skill as a painter. It would be wholly ineffectual to paint them as if they were portraits of real people with the nuances and subtleties of individual features, gradations of colour and tone. But at the same time the heads must come alive on the canvas and this requires a skill, subtle in its own way, intelligently applied to make the paint articulate form and lively character. The boldness and directness of the stare must be spot on – to carry a punch, carry the in-your-face look that’s difficult to avoid and slightly unnerving; the stare-down that provokes and challenges, that evokes an almost visceral response. The message they project so well needs no explanation or description, it’s understood, felt. It does not need to be spelt out – the faces are memorable – stick in your head. Yeadon refers to ventriloquist’s dummies and dolls (dolls are also talked to as if human), as “totemic ancestral familiars”, and in them he seems to be exploring, imaginatively and intuitively, aspects of their personality, a range of expression that reflect imaginary dialogues between the dummy and the ventriloquist. In doing so he brings them more fully into the present; gives them new life.

In as much as these heads are successful as paintings, in that they do what they were intended to do, forcefully and economically, painted with great simplicity, they do so, without the need of an explanatory text, they fulfil the role of the ‘all licensed’ critic, the spirit of carnival. What if ‘Tommy’ were real, not a fiction, not a fake human being, an artifice? He would probably be the black sheep of the family, the naughty boy, indulged perhaps, patronised probably, a figure of fun, side-lined and marginalised certainly. He might play up to the image/role projected on him, as a clown, a joker, but at the risk of not being taken seriously. The real life ‘Tommy’ would remain the perpetual naughty boy who never grows up, a comic character, a clown, a fool, who always hankers after being recognised as a serious actor. Perhaps there was something of this in the comedians, Tony Hancock and Kenneth Williams. Clive James, the wise-cracking court jester, confessed that he would always be characterised as such, and that his reputation as a poet would suffer as a consequence.

The second part of the exhibition, the landscapes, are more readily identified with the theme of Englandia. As Yeadon pointed out in his talk, Reflections on National Identity, they are like views of the countryside briefly seen as from the window of a train: images of a curving road, a railway track, golf course, cricket pitch, wind turbines and electricity pylons. The sequence of small pictures, uniform in size, and hung at regular intervals, are little windows on landscape. These are not paintings that the viewer might linger over for long. This is not to imply any deficiency. On the contrary there is still that intelligent eye at work that picks out the main features of the landscapes and also the skill that translates them into paint, but the paintings are there, primarily, I feel, to illustrate the theme of the exhibition, the various ways the countryside has become urbanised and industrialised. To bring to our attention the extent to which our ‘precious’ countryside has changed, become artificial, not ‘natural’ or ‘real’. And of course, we do not get from these paintings the detail, the richness of form, texture and incident that captures our imagination in the way a painting by John Constable (1776-1837) would, a vision of the countryside that might be absorbed over time, returned to again and again for the pleasure it gives; we still like to conjure in the mind’s eye, a countryside different from what it really is. We prefer to idealise it. Yeadon could have painted an electricity pylon or wind turbine in the middle of the cornfield in Constable’s Vale of Denham. It would have made the point explicitly enough to obviate the need to say more, but it might have deprived Yeadon the pleasure of painting the Lancashire landscape he had known as a boy, seeing and recording how, and by how much, it had changed.

Artists, writers and composers have been in part responsible for the creation and the perpetuation of myths that influence the way we see and interpret landscape. Constable lived most of his life before the advent of railways, long before the rampant industrialisation of later decades. The only industrial structure he painted was the canal at Flatford Mill, where it seems to be a natural feature of the early nineteenth century rural landscape. He makes no reference to the enclosures of common land, parcelled off to private ownership, which deprived ordinary country folk of pasture for their animals, nor does he record the economic plight of farm labourers. In the long poem, The Lament of Swordy Well, John Clare, the so-called ‘peasant poet’, bitterly condemned the changes that resulted from enclosure of land around his own Northhamptonshire village of Helpston in 1807. Constable’s landscapes have become for many the epitome of English landscape, but we should remember that in his day Constable was seen as a revolutionary. His landscapes did not conform to the idealised vision of the English countryside depicted by landscape painters of the eighteenth and early nineteenth century, painters who drew inspiration from the Classical paintings of Claude Lorraine (1600-82). English landscapes were redesigned and engineered on a grand scale at great expense and effort in order to construct an ideal that was aesthetically pleasing to the eye but entirely artificial.

These conceptions of English landscape fed into our idea of Englishness. In the early seventeenth century Shakespeare was perhaps echoing a common perception of what it was to be English and what was special about England. In Henry V, the king exhorts his troops: “On, on, you noblest English…..and you good yeomen whose limbs were made in England, show us here the mettle of your pasture; let us swear you are worth your breeding: which I doubt not” [5]. The sense of England and Englishness as particular and special, blessed even, was given vivid expression in Richard II: “…this scepter’d isle,/ This earth of majesty, this seat of mars,/This other Eden, demi-paradise,…..This happy breed of men, this little world,/This precious stone set in a silver sea,…..This blessed plot, this earth, this realm, this England” [6]. We can hear perhaps echoes of Shakespeare’s words four hundred years later in the speeches of Winston Churchill, speeches crafted to lift the spirits of the English/British at home and abroad in the conflict with Nazi Germany. In nineteenth century Germany the concept of ‘blood and soil’ become identified with what it was to be German and later with the Nazi ideal of the pure Aryan ‘master race’.

But here I am, as I now realise, writing about Englandia and national identity and not about Yeadon’s landscape paintings. Yeadon’s exhibitions always lead to debate, and on this occasion it was possible to follow up the exhibition by attending his talk entitled, Reflections on National Identity, at the Herbert Art Gallery in Coventry. Art for Art’s sake is not for Yeadon. Art is more than this. His art is one that provokes and challenges. It has a conceptual edge. The art work, always sensual, does not forget itself. As he wrote recently, “What was theory was theory, what was painting was painting” [7]. We might add, concept is concept, painting is painting. (To spell a thing out, to explain it, is not always or necessarily the best way to get a message across. There is something to be said for indirectness, obliqueness, a concept can be deeply embedded, an integral part, implicit in a work of art – the image speaks. The concept within a painting may be discovered, deciphered and interpreted over a period of time and in so doing the viewer takes possession of it – ‘finders keepers’). So let us see Yeadon as a gifted artist, whose best work is always intensely visual, more than illustration. Yeadon is an artist who is fiercely individual, with a strong social and political awareness. His art is not just to give pleasure, but to expose common preconceptions and prejudices; an art that is uniquely able to make us think and question, and, in making lasting, powerful – memorable images, an art, whether he likes it or not, that is ‘beautiful’, in the sense that, everything that we find desirable and of value, beneficial to the continuation of life, for want of a better word, is beautiful, to our eyes.

Nick Smale, February 2015

Footnotes:

1. Suitcase Act is a homage to Velázquez’s, Portrait of Sebastián de Morra, a dwarf and jester at the court of Philip IV of Spain.

2. ‘Tommy’ was made for Davenport’s Magic Shop by Leonard Insull in 1940’s.

3. Later in her career, Madame Langley performed a turn called the ‘Suitcase Act’ with her dummy, ‘Johnny’ (Green).

4. Mikhail Bakhtin, 1965. Rabelais and his World.

5. William Shakespeare. King Henry V. Act III, Scene I. King Henry to soldiers before Harfleur.

6. William Shakespeare. Richard II. Act II, Scene I. John of Gaunt to the Duke of York.

7. John Yeadon, 2015. Artspace, no 41. Alan Dyer at 70. p.16.

Other quotations not attributed above are by John Yeadon, 2015. From a Family of Ventriloquists.