Lesson 47

Originality

Nothing is original, everything has a history. Nothing comes from nothing.

[Thumbnail images – click to view]

In 1990 I began to photograph backs of heads. It was my way into photographing the body. Photography has always had a role for me in the process of making paintings, but only as a means to an end, information collection, a sort of snapshot sketchbook. This Back of Heads series was my first use of photography as a thing in its own right.

These photographs were a continuation of an investigation into paradox and contradiction. My paintings had been concerned with the carnivalesque, of the ‘world turned upside down‘. Initially the photographs of backs of heads had some of this topsy-turvy intent, that of foolishness, insult, a kind of blasphemy. The series was a perversity of portraiture, an idiotic thing, an ignorance, like a mistake and illogical. Unfortunately some of these images began to look like the photographs in a hairdresser’s window.

Back Sides, 50

I attempted to see the figure in an unexpected fashion and to ask the viewer to look at the subject differently. Reality being stranger than fiction, observation more ‘surreal’ than fantasy. Drawings can be distorted, anatomy can be transformed into something extraordinary through manipulation. I thought that the backs of heads were extraordinary in themselves, so I wished there to be little intervention. So photography was important as it was considered to be ‘real’, truthful. These Back of Heads were, I thought, new and original. Well, they were new for me.

Creativity feeling more like a discovery than invention.

Revelation as opposed to creation.

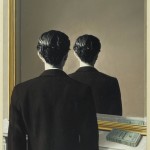

When I started to look for images of backs of heads in art history, I, of course, found many and realised that this work was far from original. Fortunately this was not important and only served to add to my interest. After all, I had discovered the back of the head independently, or rather through innocence. Anyway, my intentions were not the same as these other artists though I could see that they all recognised something of the ‘other’ in looking at a subjects back.

Surrealist Group 1924

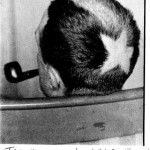

Obviously, there is a history of backs of heads as everything has a history, and nothing just pops up. There was Magritte, Mapplethrope and Man Ray’s Tonsure 1921, documenting the shaved star on the back of Marcel Duchamp’s head. I liked the way the woman’s back in a Fuseli drawing became a grotesque and absurd front.

Not to be Reproduced Rene Magritte 1937

Tonsure Man Ray 1919

Kallipyga Henry Fuseli

There was also the anonymous woman who stands next to Ferdinand VII in Goya’s painting of the Spanish Royal Family. There is a mystery to her identity, possibly a hidden ‘joke’ or of some disastrous attempt to marry off the Crown Prince; all are compelling notions. But for me, significantly, she looks away. We see the back of her head as if distracted by something more interesting than this glittering gathering. If this had been Royal group photograph, then one of their members could easily have looked the other way at the click of the shutter, but this is a painting, taking a month or two to paint. Goya’s intentionality is powerful. Could it be, that her looking the other way was a piece of deliberate idiocy on her part, or malevolence on Goya’s? *

The Family of Charles IV (Detail) Goya

Uniqueness and originality are central to the myth of the artist, central to myths of genius, and individual vision.

In Image-Music-Text Roland Barthes argues in the passage Death of the Author that literature relies on the assumption that ‘authorship’ represents the expression of a unique personality who speaks to the reader. This author is the entity in whose character the meaning and value of the text can be found.

But the text is not a unified entity.

(For ‘text’ read ‘art’ in the following quotes).

“We know now that a text is not a line of words releasing a single ‘theological’ meaning (the message of the Author-God) but a multi-dimensional space in which a variety of writings, none of them original, blend and clash. The text is a tissue of quotations drawn from innumerable centres of culture.“

Also

“A text is made of multiple writings drawn from many cultures and entering into mutual relations of dialogue, parody and congestion and this is focused at the point of the reader and not the author. A texts unity lies not in its origin but in its destination. The birth of the reader must be at the cost of the Death of the Author“.

And

“In ethnographic societies the responsibility for a narrative is never assumed by a person, but a mediator, Shaman, or relator whose ‘performance’ in the mastery of the narrative code, may possibly be admires but never his ‘genius‘“.

All Roland Barthes.

Compare this with celebrity artist Tracy Emin, who has stated that she is more famous than her work. A statement of horrific and unintended irony with reference to the ‘Death of the Author‘.

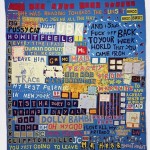

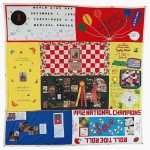

The work is not her invention, and the processes she employs are far from unique or original, particularly if we consider the derivative My Bed or her Tent which subvert female domestic labour processes that female conceptual artists in 1970s introduced. Similarly, Emin’s use of the techniques of the Names Project of the Memorial AIDS quilts.

There is a tendency to fetishise process in order to manufacture some simulacrum of originality; this in Emin’s case approaches gimmickry.

My Bed Tracey Emin 1998

Bed Mark Rodgers. Each Give a Strand… Birmingham 1996.

In 1828, Delacroix …

… painted his unmade bed, a popular theme among many 19th century painters including Adolph Mendel (1845) and John Singer Sargent, as in his ‘Studio’.

Everyone I Have Ever Slept With 1963 – 1995 Tracey Emin 1995

Mad Tracey From Margate – Everyone’s Been There Tracey Emin 1997

Named Project of AIDS Memorial Quilts 1980’s.

The problem here is not that the work has antecedents or influences, but that these are never mentioned and the work is put forward as unique and original. All her own work.

There is nothing new about appropriation – we have Picasso’s use of African masks or Warhol and Liechtenstein adopting a comic magazine style. However, in the current fashion for appropriation the art is shorn of its innovative stylistic origins, those historical, political, social factors that created the need for this change. There is nothing innovative about appropriation – appropriation is the opposite of originality.

Concepts in art are determined in a given society by what is seen as the relationship of the past or to the future. It seems that now the future is no longer a relevant notion in these ‘groundhog days‘ – the past is all that is available.

The ‘new‘ is no longer possible, if it ever was.

As with my favourite quote from Peter de Francia on the constant search for originality:

“What comes to mind…is someone flinging open the door of an antique shop and loudly demanding if there is anything new to be had.“

It has always been thus.

‘Appropriation‘ seems to accept Barthes proposition, but what is also claimed by this contemporary notion of appropriation is that the artist changes the meaning by changing the context. Of course the meaning and the context are changed, but the artist does not change the context, the context is changed for them. The artist simply appropriates the work out of context, disassociating it from its original context. The context is formed by a multiplicity of historical factors: aesthetic, political, social, ideas on progress, philosophical, ideological – none of which the current-day artist had a hand in creating. The context is ‘given’ to them, it is there already. To say that Barbara Kruger changed the context is idiotic. The artist may respond to this changing world, the artist might be part of a changing world. But they never instigated or created that change.

My issue with appropriation is that it is often not acknowledged that it has been appropriated but treated and complimented as if original and thus as a celebration of the artists’ creativity. With appropriation processes, forms and styles are shorn of their ideological reason for being. By simply ‘lifting’ these forms, the original meaning and what they originally meant is ignored. Lost are the original intentions of the artists, which was what brought these works into existence and the reason they look as they do.

These ‘appropriation artists‘ no longer invent, they curate; they are entrepreneurs who collect and put together other folks’ stuff.

Damien Hirst has recently been attracting charges of cultural appropriation by replicating a 14th century Nigerian sculpture ‘without its proper historical context‘, in his exhibition in Venice, ‘Treasures from the Wreck of the Unbelievable‘. Of course this is the point of ‘appropriating’ within this Post Modern context, and one could say the same about Picasso’s use of African masks: that of removing the original context of the works. This can be regarded as a form of colonialism, which is what took the African masks to Paris museums and the Yoruba sculptures to the British Museum in the first place. The British government has refused to ‘repatriate’ the works back to Nigeria. Originally these works would have had spiritual significance, as would the African masks. In the West they seem to take on simply formal significance, leading to racist ideas that the Ife heads could not be the work of Yoruba but only of Europeans. Hirst’s appropriation seems to aid this revisionist theory. Even if appropriation started out as subversive it certainly is not that now.

There are more questions about the Hirst appropriations in this Venice show, particularly in relation with Jason de Caires Taylor’s Grenada Pavilion. The similarity is striking, but Hirst’s work is more concerned with chutzpah and spectacle, whilst Taylor’s underwater installation can be regarded as a form of Land Art and concerned with ecology.

Hirst’s work often seems to be closer to plagiarism than appropriation, or even the term ‘copying‘ might be used. But it is not an unusual charge to be levied against Hirst. From his spin-paintings to the diamond skull, the crucified sheep, medicine cabinets, spot paintings, installation of a ball on an air jet, his anatomical figure and the cancer cell images – all been lifted and are seen as theft.

Appropriation has given the artist the ‘right’ and freedom to plunder the vast lexicon of forms and styles of history and other cultures where cultural cannibalism is the order of the day, and also to steal with impunity from ones contemporaries.

Often attributed to Picasso, it was T S Eliot who said, “good poets borrow, great poets steal“.

Art comes from art.

There is no compulsion for artists today to be original and I would contend that this has never been possible. However, not believing in the possibility of originality in art is one thing, but to appropriate another’s work and not reference or acknowledge the ‘influence‘, is another.

It seems that intellectually Barthes’ observations are accepted, but these artists do not accept the consequences of the ‘Death of the Author‘.

Simply, they want it both ways.

*Note – there is also a theory that when the Crown Prince eventually made up his mind who he was to marry, Goya could then, using the same three quarter profile – that is, using the same contour of the turned head of the anonymous woman standing next to the Prince – paint-in a portrait of this ‘new’ woman looking out of the canvas.

This entry was posted on Thursday, June 29th, 2017 at 10:39 am

You can follow any responses to this entry through the RSS 2.0 feed.